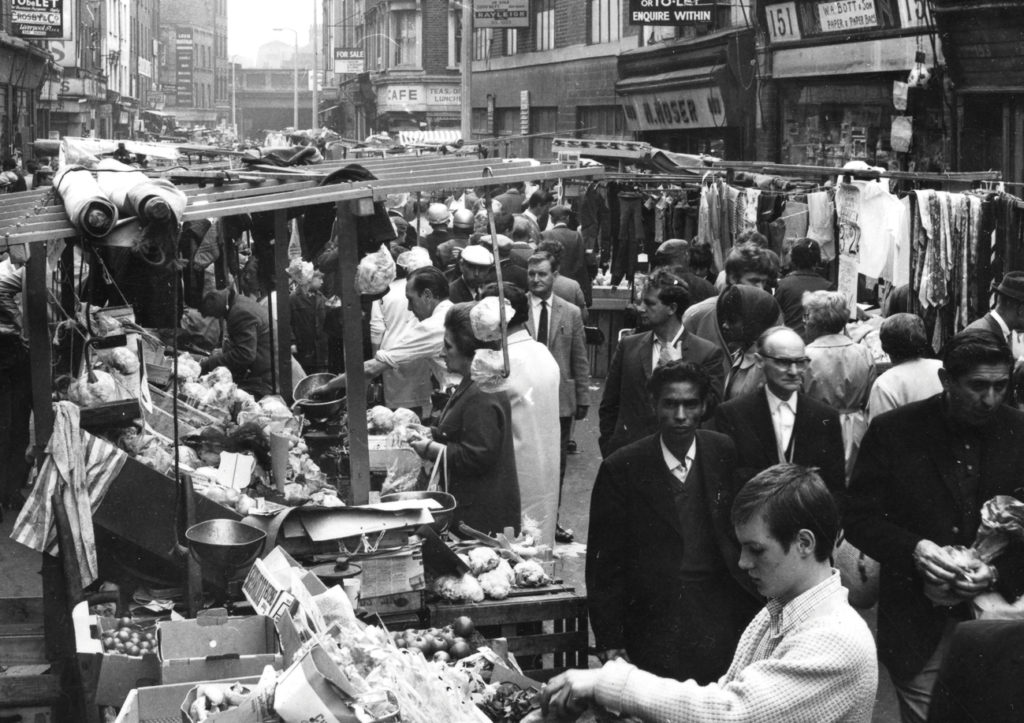

Brick Lane, located in Tower Hamlets in the East End of London, has been associated with curry and South Asian cuisine since the 1970s. Like the ‘Curry Mile’ in Manchester, the area has become synonymous with not just the food, but also the culture, and over the years has earned itself the name – ‘Banglatown’. An area, which is hugely important and symbolic to Britain’s Bangladeshi community, in much the same way that Southall known as ‘Little India’ is to the Indian community and Brixton, is to the African-Caribbean community.

Following the onset of COVID-19, just like the rest of central London, Banglatown has suffered immensely. Today Brick Lane, restaurants and shops are largely empty, as a combination of factors deter customers from venturing into the city. Something, which would be unheard of under normal circumstances. Brick Lane is normally a hub of tourists and locals, many of which are planning on having curry for their evening meal. However, Banglatown’s problems didn’t begin with COVID-19, but the virus may “be the final nail in the coffin for Brick Lane”, according to a new report.

The report which is called ‘Beyond Banglatown – Continuity, change and new urban economies in Brick Lane’, has been produced by Claire Alexander, Sean Carey, Sundeep Lidher, Suzi Hall and Julia King, and forms part of the Beyond Banglatown research project. Produced alongside the Runnymead Trust, a leading independent race equality thinktank. The initiative is focused on tracing the changing fortunes of Banglatown’s restaurants, and the implications of this change for the Bangladeshi community in East London and for Brick Lane itself.

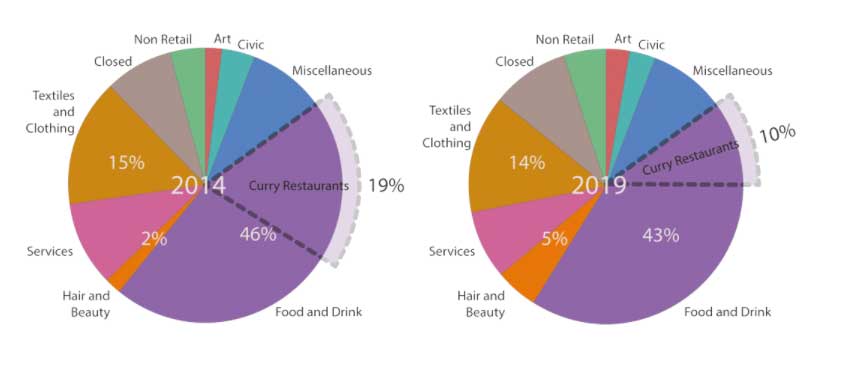

The report has revealed a steep decline in Brick Lane’s South Asian-owned restaurants that traditionally serve curry, showing a staggering decrease of over 60% in the past 15 years. In the mid-2000s there were 60 outlets compared to just 23 in early 2020. Banglatown has been transformed into something else in recent years due to a combination of gentrification and regeneration. The region’s identity has evolved now to incorporate new ‘hipster’ cafés, vintage clothes shops, delicatessens and boutique chocolatiers, all while the number of Bangladeshi-run curry eateries has plummeted.

This was all before the catastrophic impact of coronavirus. The report now calls for this heritage to be recognised and commemorated in Brick Lane itself, as well as in heritage institutions and education, otherwise this vital history may be lost to future generations. The report has also found that many restaurants have been excluded by gentrification and regeneration, and increasingly replaced by other businesses. Since the virus has struck the need for this has become even direr. While many of these problems existed before, the pandemic has exacerbated them.

Today restaurants in Brick Lane need to not only cope with the cultural shift, something that was already getting harder due to the ongoing ‘Curry Crisis’ (The reluctance of the new generation of British Bangladeshis to work in the hospitality sector), but a virus which has caused their restaurants to lose near to all custom. This, plus high rents, high rates of tax and the mayor of London’s controversial extension of Congestion Charging have made life incredibly hard. What’s worse, is due to their location and status, many restaurants in Brick Lane do not qualify for support from the Government to get them through the pandemic. With no financial aid, increased competition and no steady stream of customers, how are such businesses expected to survive?

Shams Uddin, who runs The Monsoon on Brick Lane since 2000, fears the Chancellor’s Eat Out to Help Out scheme will not be enough, saying: “Look, Rishi Sunak can cut VAT and have as many voucher schemes as he likes, but if you don’t have any customers what’s the point? People aren’t going to pay £15 to come into the city for a £10 discount on their food. It doesn’t make sense. People are looking for jobs, not discounts on their meals out”

He went on to say, “Normally, at this time of the year, the City people go on holiday and we get the tourists but because of the virus, we’ve got hardly anyone. Yesterday, we were open as usual from midday to 1am and we only had seven customers. Today, we haven’t had any at all. The landlord still wants the rent. Unless customers come back soon most restaurants in Brick Lane will only be able to survive another three or four months. This place is heading towards the coffin box without urgent help.”

Abdul Quyum Jamal, owner of Taj Store is part of a family that have occupied Brick Lane since 1936 when they opened the first Asian store in the UK. They then opened their first café Sweet Heaven, in 1976; this would later become the Taj Mahal Restaurant and Le Taj before coming under new management. Jamal told us, “The place is evolving, and it’s becoming rather arty. In a way it’s modernising; and that’s great, but we need to also protect our identity. If it changes too much it will lose its sense of community. You see people aren’t settling or putting down roots anymore.”

In regard to COVID-19 and what can be done to help; Jamal said, “We know they acted too slow to fight this virus. Everybody knows that, but these problems started way before the virus. If the Government want to help, they need to bail out some businesses. It’s the only way some will survive. The area also needs promotion again to help us attract visitors. They need to know it’s safe to come back. Let’s get on with that.”

Professor Claire Alexander, Professor of Sociology at The University of Manchester said, “The loss of Banglatown is not simply a business issue, it is about people. It represents the loss of a rich history of migration, settlement and the struggle to belong in multi-cultural Britain. The threat to the curry houses of Brick Lane, and across the country, strikes at the heart of one of the UK’s most vulnerable communities and risks decimating its central contribution to British life and culture – the British curry”

Dr Zubaida Haque, Interim Director, Runnymede Trust says: “Covid-19 has severely impacted Brick Lane’s renowned curry restaurants and cafes, which have already been decimated by gentrification, and restrictive visa requirements making it extremely expensive and cumbersome to recruit trained chefs from South Asia.” He went on to say: “On top of this the Bangladeshi-run curry restaurants are among the hardest hit by the shutdown caused by the pandemic – COVID-19 not only a health crisis it is also economic and we urge government and the Mayor of London to step in with strong business and financial support to help weather this harsh economic storm.”

The report now asks the Government to provide significant financial support to help businesses on Brick Lane survive COVID-19. Businesses in the centre of London have been overlooked and as a result, they are suffering. It also asks that the unique cultural and social heritage offered by Brick Lane’s Indian restaurants should be recognised and renewed, with investment and training within the London Plan. As well as to develop borough planning support, ideally through ground-floor property usage restrictions, capping of rents, extension of licensing hours and investment in the night time economy. And to provide training and support to restaurant owners to adapt to a changing business environment.

Finally, the report recommends that city and borough planners should recognise the hidden social and economic costs of regeneration and global investment in east London, and secure affordable social housing for low-paid workers and affordable workspaces. As well as to broaden heritage support to formally recognise the unique contribution of the Bangladeshi community to the history of Brick Lane and east London, and global London, in heritage institutions, educational provision, and the material fabric of the street.

Banglatown is an important and integral part of both Brick Lane’s history and the history of the Bangladeshi community in Britain. It also highlights the little-known history of the East End of London, and Britain itself.