Shamsuddin Khan’s influence extends far beyond having opened one of the first Indian restaurants in London, as Curry Life finds out

Shamsuddin Khan, now in his 80s, has experienced first-hand the many changes in Bangladesh’s political, historical and cultural landscape. But it’s not from being in the country itself, as one might imagine, where he’s seen these changes, but rather from a corner of south west London – Clapham to be precise.

It’s here you’ll find Maharani restaurant. Khan has been the owner for the last 65 years, ever since it opened in 1958, and deservedly has a reputation as one of the UK’s founding curry restaurateurs. But Maharani – and Khan aren’t just known for putting London on the map for Indian food – the restaurant was also a gathering place for the Bangladeshi community in the 1970s and early 1980s, particularly for supporters of the Awami League political party. Khan was the founder of the UK arm (while not involved today, he is still very much respected by existing members of the League) and his ties with the party led to a close friendship with Sheik Hasina, the current prime minister of Bangladesh.

Her father and other members of her family were assassinated in 1975 while she was away in Germany; as the exiled opposition leader following her father’s death, she visited London, found her way to Maharini and often stayed with Khan and his wife in their home, just a few minutes’ drive away from the restaurant.

Opportunity knocks

It’s in that very same house, in a modest living room, where Khan is speaking to Curry Life, sharing some of the more colourful moments from his fascinating life story. He first came to London when he was 17, finding work in an Italian restaurant in Soho’s Old Compton Street. Over two years, he honed his restaurant skills, moving from the kitchen to front of house, perfecting the art of making tea, and eventually moved on to work at Jaipur, an Indian restaurant in Shepherds Bush. At the age of 20, together with business partners, he then bought the leasehold to an existing Italian restaurant in Clapham, which eventually became Maharani.

At the time the area, much like other parts of London, was run down and curry was something of a novelty. Khan even recalls having to procure spices from unusual places, such as the local chemist and having to grind them himself. Word soon spread, however, about the cuisine and as Khan says, many people were attracted as they had colonial ties to India, having previously visited or worked in the country. Business picked up a few years later, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when many parts of London were regenerated under then UK prime minister Harold Wilson’s Urban Programme.

“People became more interested in trying Indian curry – we had our menu on a blackboard, with prices and items, just a few dishes including chicken curry,” recalls Khan, who managed the front of house. “The restaurant was busy every Friday and Saturday, and was packed after the pubs and clubs shut.”

Most of the Indian restaurants at the time were based in London’s West End (Veeraswamy in Regent Street is often credited as the being the oldest in London, having opened in 1926), so Maharani was able to establish itself as a restaurant that people were keen to travel to. Khan says that at the time, people were happy to help others out. He was even called the ‘Young Governor’, with many people coming to visit, impressed by the young entrepreneur and what he had already achieved.

Well-connected

It seemed a natural progression for the restaurant to become a hub, a place where many Bangladeshis gathered to exchange ideas, particularly with Khan’s ties to the Awami League, and by 1973, Khan had purchased the freehold and bought out his previous business partners.

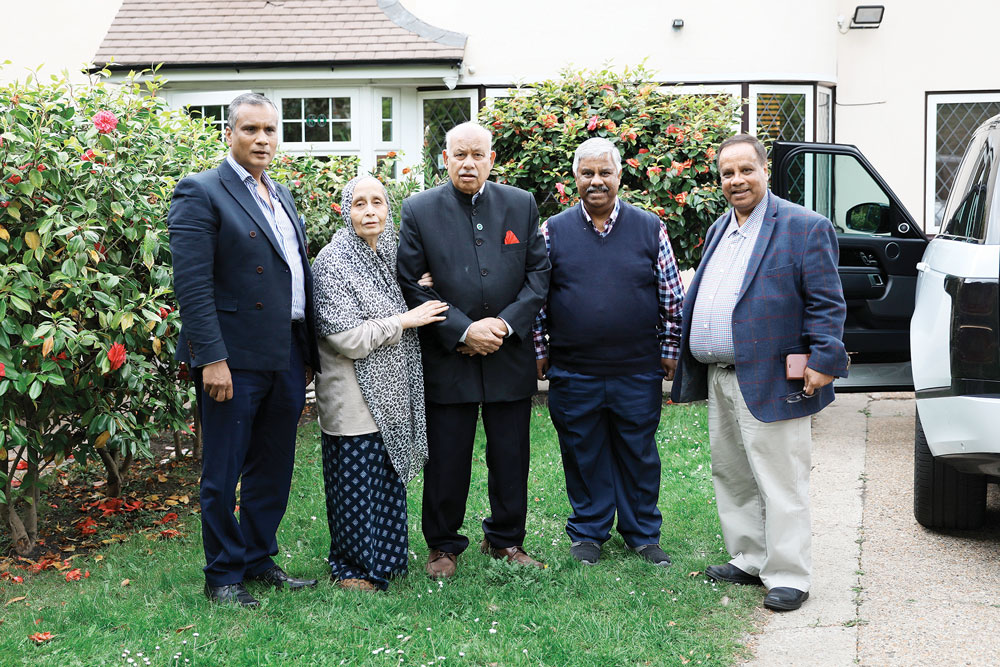

Mrs Sofrunnessa Khanom and Mr Khan

With Chef Atul Kochhar

“There were still not many restaurants at that time so Maharani became a community space for supporters of the League – that’s how I became connected to Sheik Hasina,” explains Khan.

The restaurant also grew a very loyal customer base, many of whom still visit today, some travelling long distances. Khan remembers one particular customer who was seven years old when he first visited; he has since moved away from London but visits with his own children from time to time when he is back in London.

Today, Maharani is as popular as it was all those years ago, and the menu features a mix of dishes such as Madras, Korma and Bhuna curries alongside house specials such as Shorisha Murg, (described as hot, spicy with mustard paste), Murgh e Zoyton (chicken tikka flavoured with olive & fresh spices, slightly hot), Gost Kata Masala (Diced lamb pieces cooked in a special sauce made from yogurt & fresh herbs) and Chicken Rajeshwari (cooked with fresh herbs, tomatoes, chutneys, coriander, ginger, garlic and green chillies).

The restaurant has also attracted its fair share of celebrity diners, including the actor Pierce Brosnan and television presenter Sarah Kennedy. It’s also won numerous awards and expanded over the years. In 2002, due to ongoing demand, Khan bought the site adjoining the restaurant and the restaurant now offers 150 covers. Other restaurants followed too – a total of 11, within London or close to the capital, including takeaways but Khan now only operates two – the existing Maharani and another one based in Camden, which is managed by his nephew, Abdul Karim Nazim. Alongside the catering industry, Khan is also involved in a cash and carry business in London’s east end, owns properties and several tea plantations in Bangladesh and has also contributed to a number of charitable endeavours.

Facing the future

While Khan has carved out an impressive business empire, Maharani is where it all started and it’s clear to see that he is finding it hard to let his business go; he visits the restaurant most evenings and says he feels uneasy when he is not there. Talking about his succession plans is difficult too as none of his three children (two sons and a daughter) are interested in the restaurant industry or have any intention of taking over the business, having carved out successful careers in completely different sectors – within the foreign office, education and aviation.

It’s a common problem faced by many within the industry. Bangladeshi restaurant operators are finding out their children who have been brought up and schooled in the UK have little interest in learning a trade they perceive as involving long hours and perhaps not as well paid as other careers. They also have less ties with their mother country and therefore perhaps less of an emotional connection with their parents’ businesses. The curry sector is also facing other issues such as a continued squeeze on margins and Khan believes there is no easy solution to help improve the sector’s outlook, but suggests that the use of buffets and the way food is presented need to be addressed. And what of Maharani’s future, given that Khan has been at the helm for more than six decades now? With two nephews currently working with him, Khan is hopeful that the Maharani name will continue to make an impact for years to come.