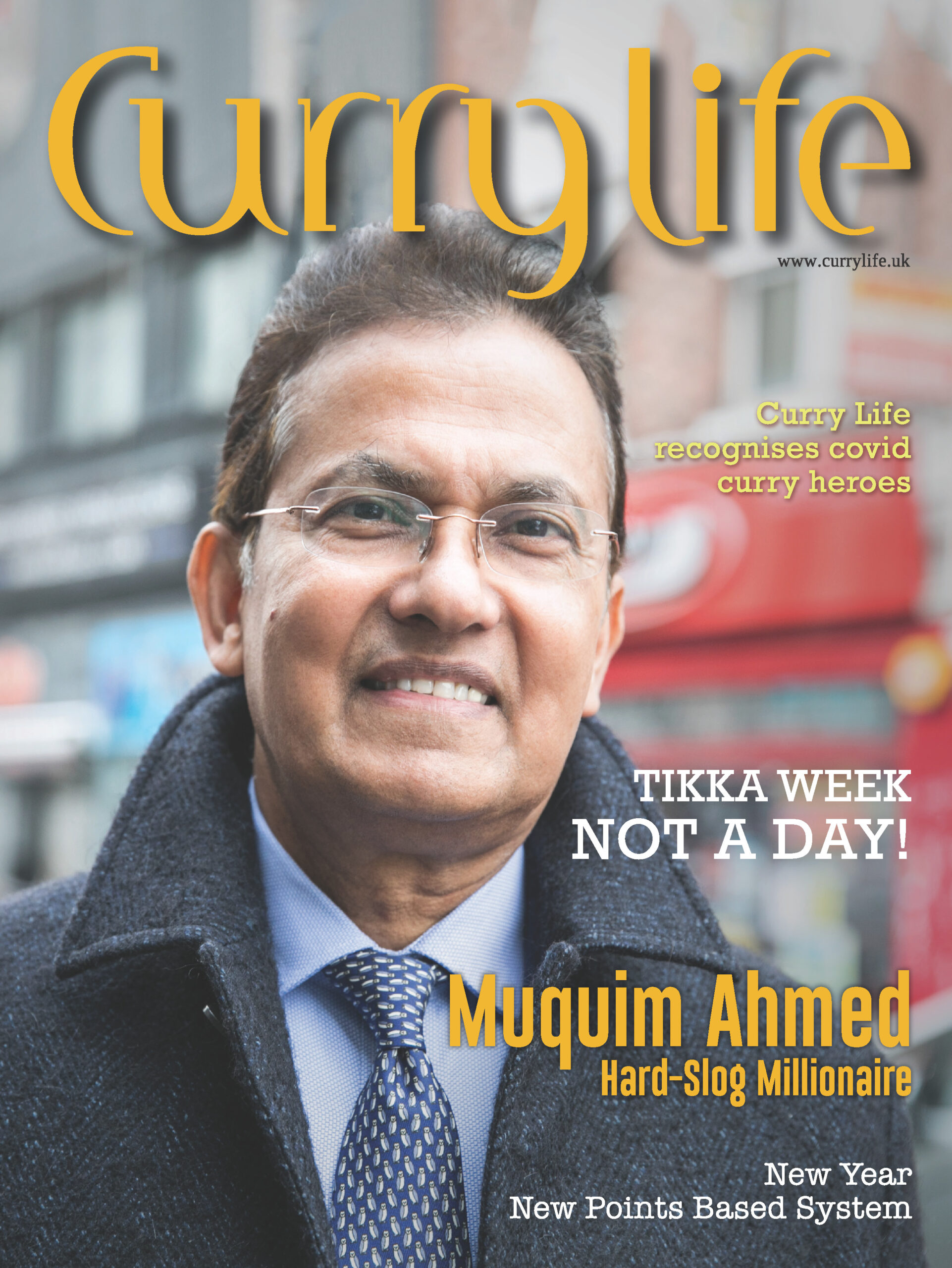

MUQUIM AHMED Hard – Slog Millionaire!

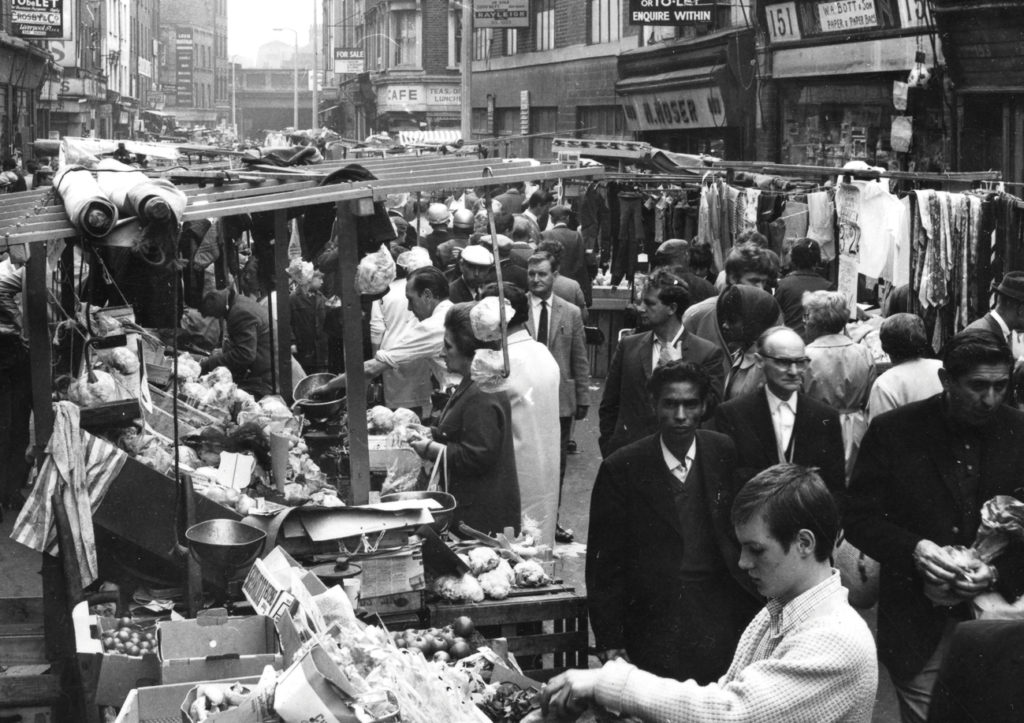

Muquim Ahmed has spent the past 40 years building a burgeoning business empire – which has seen the millionaire businessman dubbed as the King of Brick Lane. Here he tells Curry Life how he has risen through the ranks – putting his success down to tenacity and being in the ‘right place at the right time’.

“I am a restless person, I need to be doing something all of the time,” Muquim Ahmed tells me, not five minutes into our meeting. We’re gathered (socially-distanced style) at Ahmed’s offices at Canary Wharf in east London on a dreary, rainy day.

Pre-Covid, the area would be buzzing but the offices are eerily silent and empty. Reassuringly though, the biggest presence is from the cleaning crew. Such an atmosphere, however, does little to dampen Ahmed’s enthusiasm; he is clearly a person who is constantly on the go, no matter the situation.

In the last 40 years, he has built a business empire spanning a myriad of industries – from electronics, to hospitality, from travel to finance, from wholesale distribution to catering, among others. He is currently chairman of Quantum Securities, a substantial property portfolio business, worth millions, established decades ago consisting of both residential and commercial properties.

Ahmed attributes his success to tenacity and endurance and the belief that when setting up your goal in life, you need to aim high. His current position at Quantum Securities is also in recognition of his vision of the long-term. As he puts it, ‘the service industry, trading and jobs have a limited shelf life, but assets, property and shares will always have a greater continued growth value for generations.

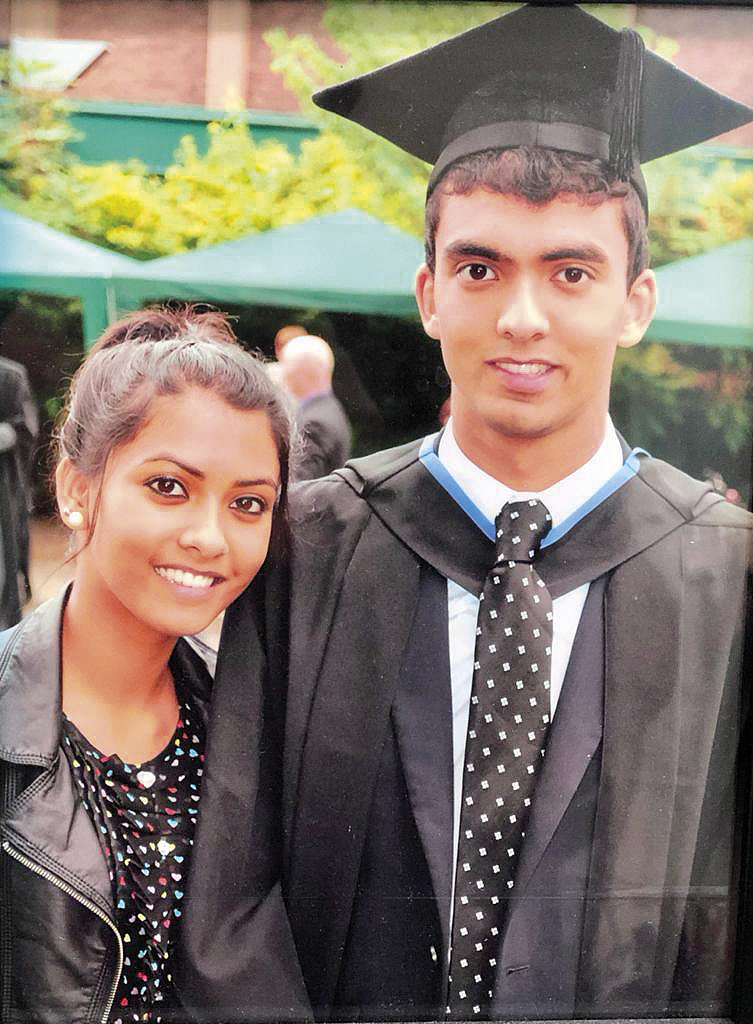

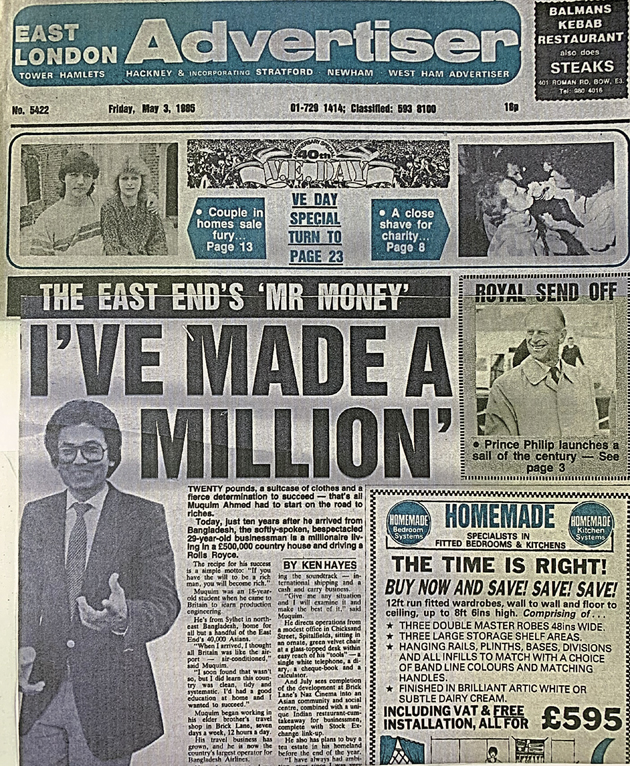

Ahmed is also an avid gardener, which presumably helps him to unwind from his business interests. He is a proud owner of a stately garden. Yet he is perhaps best known for being dubbed ‘the first Bangladeshi millionaire’ and the ‘unofficial king of Brick Lane’, credited with helping to transform the area in London’s East End into a vibrant hub in the 1990s. Various press reports documenting his rise have referenced his ‘fierce determination to succeed’, his ‘boy wonder’ personality and his hunger for business. He has appeared in the Estates Gazette and Asian Rich list which highlighted his achievements as a self-made millionaire and how he has raised the profile of the Bangladeshi community.

He appeared in the Sunday Times Rich List, the definitive list of the richest people in the country. Presently, research shows in the Companies House that his fixed assets supersede by millions within his peer group.

Even with 40-plus years of business under his belt, Ahmed is still as passionate about business now as he was then, with the firm mantra that you have to believe in yourself if you want to achieve something. Like many before him, Ahmed arrived in the UK from Bangladesh in 1974 to finish his engineering studies. As he explains, there was – and still is – a belief in his home country that if you don’t go abroad and study, it can become difficult to get a good job back home.

“The high earning, doctors, the lawyers [in Bangladesh], they were all educated abroad; my parents wanted me to be someone important in the community so they sent me to England to complete my studies,” says Ahmed.

His studies, however, were soon abandoned in favour of several business opportunities, such as exporting electrical goods from the UK to his native Bangladesh, and acquiring the lease first and later the freehold of Naz Cinema in Brick Lane. Ahmed admits being in the right place at the right time. He imported movies from Bangladesh and showed them on the big screen at the cinema, gaining a loyal following among the Brick Lane locals.

Ahmed was also quick to spot how to make a thriving business better, reflecting his determination to go further. Noting that there was a huge demand for electrical goods, he looked at how to improve margins, recognising the Far East’s potential. This led to his move into wholesaling, sourcing products mostly from Hong Kong factories. These included watches, radios, clocks and cassette players, all under the brand name of Harper (chosen because Harper sounded more English and branding was for UK customers) and other electrical accessories. His Sylto Cash and Carry attracted customers from far and wide and established itself as a national distributor for popular Japanese brands such as TDK, JVC, Panasonic and Casio. In the late 1980s he was also instrumental in raising the profile of the community by helping out Notun Din and later – the weekly Asian Post English newspaper.

Survival instinct and being a role model

Ahmed is also a survivor – in more than one sense of the word. In October 1994, his warehouse at Chicksand Street, just off Brick Lane, burnt down to the ground, with his Christmas trade – one of the most lucrative times of the year, literally going up in flames. The accidental fire destroyed the entire Sylto business, as well as the offices housing his media and other companies, incurring losses of over £4m.

Undeterred, Ahmed turned to what he had left – the cinema, where the concept for the Cafe Naz chain of restaurants took hold, having opened the first such restaurant in the former cinema’s foyer. He opened another nine restaurants, with same theme and name, all around the country within five years of opening the first. Once again, Ahmed was looking to capitalise on a growing demand in the UK – this time for Indian food and the popularity of dishes such as chicken tikka masala.

Cafe Naz quickly built a following among diners and restaurant critics for its take on contemporary Indian cuisine, providing authentic-tasting dishes highlighting the flavours of regional Indian cuisine. Ahmed brought in top chefs from five-star hotels in India and Bangladesh, with the restaurant not only showcasing authentic cuisine but Indian culture too. Chefs shared recipes with customers while the restaurant provided Indian-themed entertainment, as well as organise a number of food festivals.

In April 1999, Ahmed narrowly escaped death during the ‘Brick Lane bombing’, an attack targeted at London’s Bangladeshi community. There had been two similar nail bomb attacks in the run up to the one on Brick Lane, targeting Brixton’s black population and the LGBT community in Soho. Just moments before the bomb exploded, in the trunk of a car parked outside Cafe Naz. Ahmed had been at the restaurant. It was destroyed by the bomb, with Ahmed putting his narrow escape down to sheer luck – he was seating by the window which took the brunt of the force of the blast as the front and back house was preparing for the lunch trade when his wife Rashmi called and he crossed the road to meet her and their five year old daughter Monique just as the blast went off.

So how did Ahmed bounce back from such life-changing events such as his warehouse being destroyed and the bombing? Following the devastating warehouse fire, he was lucky enough to be able to borrow money from his family and his brother-in-law to get himself back into business, but crucially, his success has been about spotting an opportunity and running with it, as well as knowing when it’s the right time to move on. Muquim’s former wife Rashmi Ahmed also played an important role to support him to meet new challenges in business. After fire he did not try to rebuild Sylto for example, moving on to Cafe Naz. By 2000, a year after the bombing, there were 10 such restaurants under the ‘Naz’ brand, across various locations such as London, Cambridge, Horsham, Cardiff and Chelmsford. After 20 years of successfully running the chain of Café Naz, he decided to exit from Restaurant trade recognising he had taken that opportunity as far as he could. He is still involved in a handful of restaurants through Quantum Securities, but this time as their landlord.

“There were several reasons to get out of the restaurant industry,” he says. “There was personal stress, gross profit margins became lower, we suffered from staff shortages and the European HACCP & laws. It became harder to ensure the chefs are properly trained and you can’t be everywhere – sometimes too much can be just that.”

Ahmed had also established a bakery and a food manufacturing business alongside running Cafe Naz. With several of his restaurants preparing thousands of meals every week, moving into the industrial production of ready meals seemed like a natural progression – and one which again filled demand at the time for ready-cooked meals. The warehouse Ahmed purchased for his ready meal production facility turned out to be a lucrative move – he sold it for more than three times the purchase price, which led him to where he is today – property investment under Quantum Securities.

So what would Ahmed say to the younger generation? His advice is simple: identify what you are good at and what you enjoy doing, Believe in yourself and do your best and give it your best shot. If you have ‘it’, don’t give up and if you are not successful, keep on trying.

“It’s essential to aim high, but not too high that you cannot reach,” he says. “To retain success is an art in itself. Be focused, diligent and plan your enterprises in a structured way. Ambition and motivation and a desire to succeed should propel you to your destination.”

And if the warehouse fire taught him anything, Ahmed says it’s that no matter how hard you try, accidents can happen. “Consolation and encouragement does go a long way, and you can feel incapacitated and debilitated. You’ve got to pick yourself up again; it’s difficult, but life must go on.”

Political point

A firm remainer during the Brexit process, Ahmed feared that if the UK left the European Union, the country would suffer from a number of issues, labour shortages for example being his main concern. He has since changed his mind however, and says that leaving the EU is a better position for the UK to be in.

Only time will tell whether or not this is the case, but one thing is certain: as a businessman, Ahmed is proud to give his support to a Conservative government and has campaigned for the party over the years in a number of general and local elections. He was the co-founder of Conservative Friends of Bangladesh, an organisation that aims to develop relationships between the Conservative party and the British Banglasdeshi community. Currently he is serving as the Patron of CFOB.

“When you are faced with a situation like Brexit, everyone looks after their own interests,” he says. “I am convinced now that we will be more successful on our own. I believe in meritocracy – in a socialist-type state, there is no incentive for the individual to thrive.”

Unsurprisingly, we touch on immigration – a subject very close to Ahmed’s heart, who says the current situation is ‘far,’far better now than some 40 years ago’ when he first arrived. Without immigrants, he says, he would not have been able to run his businesses. “Immigrants come here with nothing – just their hopes and aspirations, they make a life for themselves here by working hard,” he says. “If you have the ability and determination you can achieve anything;

you can be anywhere if you have this belief in yourself.”

Community action

Working with and for the local community is another of Ahmed’s passions. He is adamant about having worked hard to make a difference to the lives of those in London’s East End, and helping the Bengali community integrate into mainstream British society.

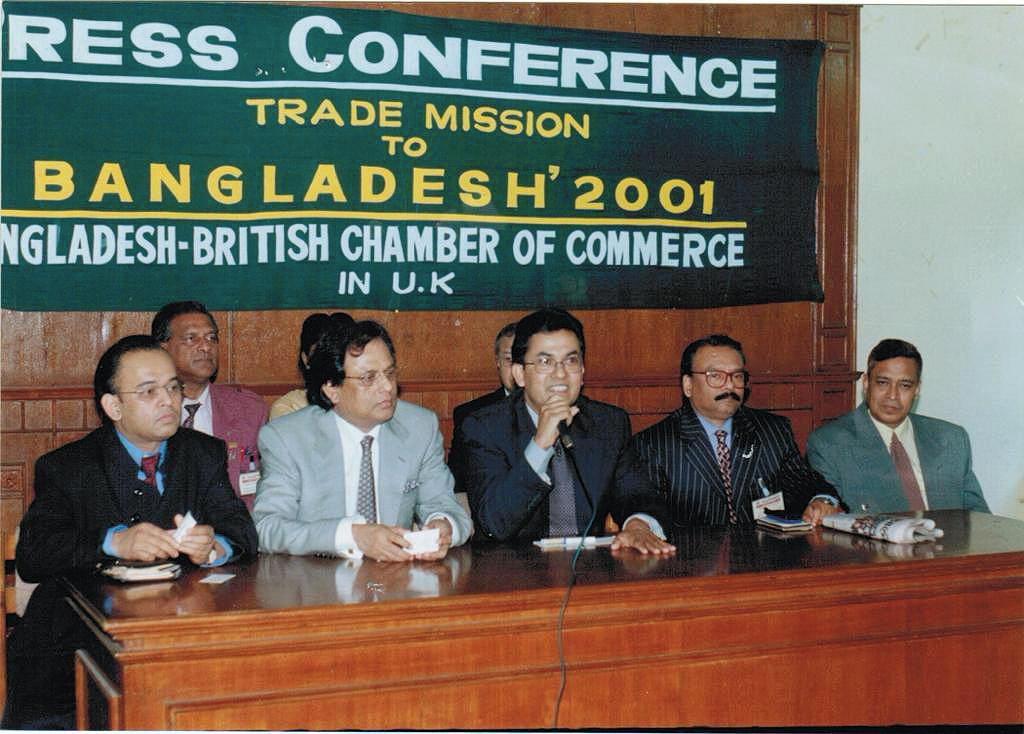

Ahmed was previously the chairman of the British Bangladesh Chamber of Commerce (serving three terms), and played a prominent role, overseeing a number of seminars and trade exhibitions, including The Expo Bangladesh 2005, held at London’s Barbican Centre, the first ever one-country trade show held internationally by Bangladesh. This helped to raise the profile of the Bangladeshi on an international front.

His take is very much that leadership is about actively lifting people up to your level, not just showing people how you got there. “Our community is a new community, we have been here not even 60 years and we have achieved glowing heights. In the field of politics, we have four member of Parliament, we are in the House of Lords, Queen’s Councillors, Judge, Doctors, Scientist and City High flyers, High Commissioner/Ambassadors in the British foreign service. We are a young and vibrant community and are certain to achieve many more distinctive heights in the years to come.

Read more

THE SOUL OF A COMMUNITY I-Naga Restaurant

The last few months have been undeniably challenging for the restaurant industry, with lockdowns and tier changes creating a rollercoaster of openings and closings across the country. Every day brings more stories of the ruin of businesses that have been years in the making and apprehension about the future. Deep in South London, however, is a heart-warming success story thanks, in part, to the huge affection and respect it holds in its local community. I-Naga, in West Wickham, a short drive from bustling Bromley town centre, is the lovechild of British-Bangladeshi chef Abdul Hay and is known for both its award-winning menu and charismatic owner who is somewhat of a celebrity in local circles.

The 43-year old entrepreneur opened the contemporary curry house 10 years ago after ‘the existing restaurant had fallen into a bad way.’ According to Abdul. ‘I saw the potential and wanted to rescue it. I was able to buy the place for a song which made it possible and have not looked back’. Having been born in Sylhet in eastern Bangladesh, Abdul arrived with his parents aged three and cut his teeth in the curry trade working at his older brother’s takeaway in East London. Now married to housewife Nargis and the father of 4 sons, aged between 6 and 18, Abdul commutes tirelessly each day from his home in Bethnal Green, ‘seven days a week and nearly every day of the year’.

Bangladeshi cuisine has long been associated with the thriving ‘bhuna and beer’ cultures of Brick Lane and Birmingham, so beloved by British office parties and stag dos. However, Abdul has, in this traditional corner of the London suburbs, been quietly elevating his ancestral food to a whole other level. ‘I grew up, and still live in Tower Hamlets, the heart of the Bengali curry industry in the capital,’ reflects Abdul. ‘I saw how the local restaurants diluted their heritage to suit British tastes and, while I understand it in my head, my heart wanted to create a curry house that would not compromise but would win over my diners by sheer quality and taste.’

This approach, infused with authenticity and passion, has clearly paid off. A short time after opening, the restaurant was the very first in Bromley to hold a five-star hygiene rating. Within a year, it had won its first Curry Life award and I-Naga’s Head Chef, Abab Miah, has been the winner of Curry Life’s Curry Chef Of The Year award for four consecutive years. I-Naga was described to me by the editor of this magazine as ‘probably my favourite curry house in the country. I even missed it when I was working in Delhi’. High praise indeed, so I started the journey from my West London home with high expectations.

Arriving on a rainy evening, I was immediately enveloped in Abdul’s warmth as a host. It felt as though I had walked into his own family home and was being treated as a long-lost friend. ‘When I open my doors at 5pm’, agrees Abdul, ‘I am opening my doors to my guests and cannot help but treat them as though they are sitting at my own table’. Meaningful engagement, however fleeting, is so valued in our current times. Diners, starved of much of their usual social interactions, will be more appreciative than ever of a warm welcome and a personal touch. Abdul has this in spades and, in a relatively recent timespan, has built a devoted following. This was evident in the stream of takeaway collections as I sat down to my table, the only diner in the closed restaurant. The staff seemed to know most people by name and orders were interspersed by cheerful enquiries into relatives’ health and Christmas plans. After months of social distancing and isolation being pressed on us in the fight against Covid, this atmosphere of authentic community is sure to be in demand. Who wants sterile formality and insincere service after what we have all been through?

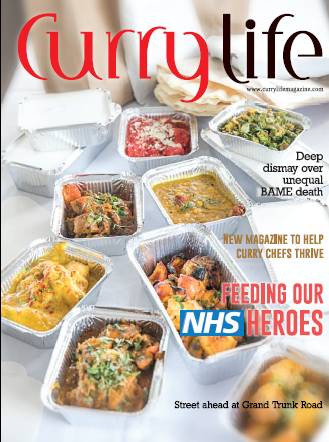

Abdul is proud of his standing in the community, forged through both I-Naga’s popularity and his tireless giving back to the area. ‘I take great pleasure in sponsoring most of the local sports teams’, says Abdul, ‘I contribute a significant amount of money each year to them because I know such activities are crucial to keeping a community alive and thriving.’ I also hear about the restaurant’s feeding of NHS staff in the A & E department of the nearby Princess Royal University Hospital and providing lunches for local schools, including a regular buffet meal for school children.

They say what goes around comes around and the restaurant owner certainly had a taste of this after a burglary last year. ‘The local response was overwhelming. It still blows my mind’, reflects Abdul, ‘I refused a kind offer of a GoFundMe page being set up and so the locals began to flood the restaurant, I mean queues out the door. One man ordered food from me for 14 days straight, admittedly by the 12th day, he laughed about a curry overload!’. ‘I will always be grateful to our neighbourhood for that time which showed me the power of human kindness like nothing else. I am just a regular guy with a dream but God is definitely watching over me’.

Abdul cites inspirations such as Gordon Ramsay as examples of a fearless drive achieving anything. But there is no doubt he also puts the graft in: ‘Nearly every dish that leaves my kitchen is seen by me. I know this to be a secret to success. I also refuse to use anything but the highest quality ingredients. My chicken is from a Smithfield Market butcher, the freshest anywhere, the lamb is from New Zealand and basmati rice is only Tilda. Yes, it may cost more, but you know in the first bite what you are being given.’

The recently refurbished dining room of I-Naga is pleasingly spare, a refined canvas for the colourful dishes on the menu. The long dining room, with divided tables that feel suitably safe, is decorated in a neutral palette complemented by glamorous lighting and crisp, heavy white table linen. The bar is well stocked against lit-up glass and the whole effect is quietly luxurious without being flashy. With a flourish Abdul produces the menu – the scope of which is immediately eye-catching and talks me through some of his highlights. The salmon tikka is, according to the chef, ‘mouth-wateringly good’, and a quick Google reveals his public feel much the same. Sadly, I am allergic to fish and so had to pass on this delight but Abdul assured me even better was to come. And how right he was! Full disclosure, I have lived or travelled in India for nearly 20 years and I have never experienced a poppadom like the one that was produced as an amuse bouche by a smiling Abdul. A thin soft ‘papad’ was covered in a vibrant layer of tamarind, crispy red onion, channa and, even, the crunch of Bombay Mix. I could only stare at it for a few minutes in interest and slight suspicion before the first (incredible) mouthful. Safe to say, I will never be satisfied by a bare naked poppadom again after this explosion of taste, tanginess and creativity. One of the great crimes of mid-range Indian restaurants in the UK is a complete absence of surprise. This is where I-Naga is leading the field and raising the bar for curry houses everywhere.

Having thought we might have peaked with the fully-loaded poppadom, the next course, a petite plate of smoky rich red Chicken Tikka, topped with a voluptuous king prawn (although sadly I could not eat this) and caramelised sweet onion brought everything crashing to a halt. Even allowing for the gastronomic banality of lockdown life, that delicate starter was, hands down, the best thing I ate in 2020. Such a familiar dish, one that I have indulged in in palaces, dhabas and streetcarts, from Lahore to Kolkata, and yet here in the fringes of Bromley, I find the most exquisite example of it I can remember. Subtle and delectable like the courtesan Pakeezah herself. As a non-driver, Google Maps tells me it is 1 hour 9 minutes, taking in a tube, overground train and suburban bus, from my front door to I-Naga. That is a journey I would willingly do again and again, in all weathers, for this one, transcending, starter.

Abdul and his team are extremely attentive but keep the balance just right allowing space for the dining experience while never more than a smile away. Still coming down to earth from the tikka, I was ushered into another taste realm, with a flaky rolled paratha filled with meltingly tender spiced lamb. The changing of gears worked well and the lamb was warm, comforting and as though it might have been cooked in a clay tandoor for 24 hours. It felt like sitting at dusk in a wood-smoked North Indian village watching the fields and mango trees, it felt like being a prized guest, it felt like celebration, it felt like home. I was beginning to see the strength and magic of I-Naga, it takes the diner on a journey through these small plates of storytelling. For the British, it will be Jewel-in-the-Crown, Golden-Triangle exotic while for the South Asian diaspora, it is nostalgia, the daadi on a charpoy shelling beans, soul food. Either way, Abdul has built so much more than a restaurant on this corner of Croydon Road. It is a magic carpet.

Beaten-brass karahi dishes come out laden with Anglo-Indian Chicken Curry, thick, mildly spiced and aromatic – I can easily imagine ayahs feeding it to plump children of the Indian Raj – and perfectly flavoured basmati rice. Wanting to explore further into Abdul’s local heritage on the menu, I requested one of the chef’s signature dishes, a fiery Garlic Chicken Tikka, in a velvety sauce – it did not disappoint and was a perfect high note to a memorable meal. Dessert was a sweet tongue refresher in the form of Pistachio-infused kulfi, as creamy and fresh as anything served on Chowpatty beach at sunset.

Abdul likes to say that ‘a good customer will never leave a bad review; if he is unhappy with a meal and feels he has been undersold, he simply won’t return.’ There is no danger of that from this reviewer – I am already looking forward to going back and sampling Abdul’s original homestyle Bengali Chicken Korma, in which according to the chef, ‘there are no coconut or almonds, the ghee does all the talking and you haven’t lived until you’ve tried it’. This year will see Abdul launching a weekly Bengali curry night and bringing more secrets from his family kitchen to lucky diners. 2021 is looking up already.

I-Naga Restaurant, 84 Croydon Rd, Coney Hall Roundabout, West Wickham BR4 9HY

Read more

Saving Brick Lane The UK’s Curry Capital

Brick Lane, located in Tower Hamlets in the East End of London, has been associated with curry and South Asian cuisine since the 1970s. Like the ‘Curry Mile’ in Manchester, the area has become synonymous with not just the food, but also the culture, and over the years has earned itself the name – ‘Banglatown’. An area, which is hugely important and symbolic to Britain’s Bangladeshi community, in much the same way that Southall known as ‘Little India’ is to the Indian community and Brixton, is to the African-Caribbean community.

Following the onset of COVID-19, just like the rest of central London, Banglatown has suffered immensely. Today Brick Lane, restaurants and shops are largely empty, as a combination of factors deter customers from venturing into the city. Something, which would be unheard of under normal circumstances. Brick Lane is normally a hub of tourists and locals, many of which are planning on having curry for their evening meal. However, Banglatown’s problems didn’t begin with COVID-19, but the virus may “be the final nail in the coffin for Brick Lane”, according to a new report.

The report which is called ‘Beyond Banglatown – Continuity, change and new urban economies in Brick Lane’, has been produced by Claire Alexander, Sean Carey, Sundeep Lidher, Suzi Hall and Julia King, and forms part of the Beyond Banglatown research project. Produced alongside the Runnymead Trust, a leading independent race equality thinktank. The initiative is focused on tracing the changing fortunes of Banglatown’s restaurants, and the implications of this change for the Bangladeshi community in East London and for Brick Lane itself.

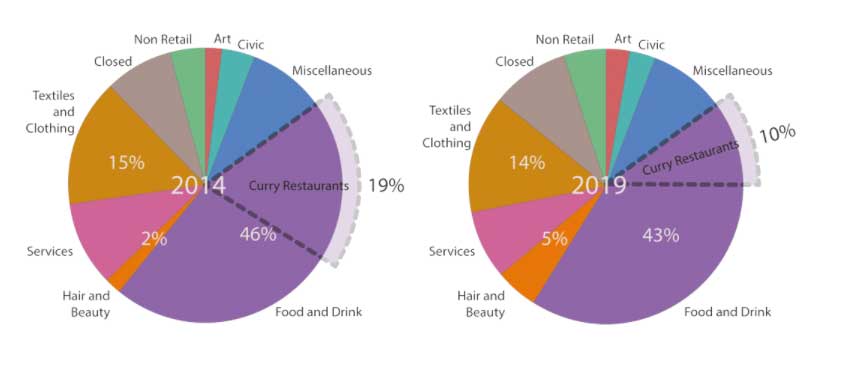

The report has revealed a steep decline in Brick Lane’s South Asian-owned restaurants that traditionally serve curry, showing a staggering decrease of over 60% in the past 15 years. In the mid-2000s there were 60 outlets compared to just 23 in early 2020. Banglatown has been transformed into something else in recent years due to a combination of gentrification and regeneration. The region’s identity has evolved now to incorporate new ‘hipster’ cafés, vintage clothes shops, delicatessens and boutique chocolatiers, all while the number of Bangladeshi-run curry eateries has plummeted.

This was all before the catastrophic impact of coronavirus. The report now calls for this heritage to be recognised and commemorated in Brick Lane itself, as well as in heritage institutions and education, otherwise this vital history may be lost to future generations. The report has also found that many restaurants have been excluded by gentrification and regeneration, and increasingly replaced by other businesses. Since the virus has struck the need for this has become even direr. While many of these problems existed before, the pandemic has exacerbated them.

Today restaurants in Brick Lane need to not only cope with the cultural shift, something that was already getting harder due to the ongoing ‘Curry Crisis’ (The reluctance of the new generation of British Bangladeshis to work in the hospitality sector), but a virus which has caused their restaurants to lose near to all custom. This, plus high rents, high rates of tax and the mayor of London’s controversial extension of Congestion Charging have made life incredibly hard. What’s worse, is due to their location and status, many restaurants in Brick Lane do not qualify for support from the Government to get them through the pandemic. With no financial aid, increased competition and no steady stream of customers, how are such businesses expected to survive?

Shams Uddin, who runs The Monsoon on Brick Lane since 2000, fears the Chancellor’s Eat Out to Help Out scheme will not be enough, saying: “Look, Rishi Sunak can cut VAT and have as many voucher schemes as he likes, but if you don’t have any customers what’s the point? People aren’t going to pay £15 to come into the city for a £10 discount on their food. It doesn’t make sense. People are looking for jobs, not discounts on their meals out”

He went on to say, “Normally, at this time of the year, the City people go on holiday and we get the tourists but because of the virus, we’ve got hardly anyone. Yesterday, we were open as usual from midday to 1am and we only had seven customers. Today, we haven’t had any at all. The landlord still wants the rent. Unless customers come back soon most restaurants in Brick Lane will only be able to survive another three or four months. This place is heading towards the coffin box without urgent help.”

Abdul Quyum Jamal, owner of Taj Store is part of a family that have occupied Brick Lane since 1936 when they opened the first Asian store in the UK. They then opened their first café Sweet Heaven, in 1976; this would later become the Taj Mahal Restaurant and Le Taj before coming under new management. Jamal told us, “The place is evolving, and it’s becoming rather arty. In a way it’s modernising; and that’s great, but we need to also protect our identity. If it changes too much it will lose its sense of community. You see people aren’t settling or putting down roots anymore.”

In regard to COVID-19 and what can be done to help; Jamal said, “We know they acted too slow to fight this virus. Everybody knows that, but these problems started way before the virus. If the Government want to help, they need to bail out some businesses. It’s the only way some will survive. The area also needs promotion again to help us attract visitors. They need to know it’s safe to come back. Let’s get on with that.”

Professor Claire Alexander, Professor of Sociology at The University of Manchester said, “The loss of Banglatown is not simply a business issue, it is about people. It represents the loss of a rich history of migration, settlement and the struggle to belong in multi-cultural Britain. The threat to the curry houses of Brick Lane, and across the country, strikes at the heart of one of the UK’s most vulnerable communities and risks decimating its central contribution to British life and culture – the British curry”

Dr Zubaida Haque, Interim Director, Runnymede Trust says: “Covid-19 has severely impacted Brick Lane’s renowned curry restaurants and cafes, which have already been decimated by gentrification, and restrictive visa requirements making it extremely expensive and cumbersome to recruit trained chefs from South Asia.” He went on to say: “On top of this the Bangladeshi-run curry restaurants are among the hardest hit by the shutdown caused by the pandemic – COVID-19 not only a health crisis it is also economic and we urge government and the Mayor of London to step in with strong business and financial support to help weather this harsh economic storm.”

The report now asks the Government to provide significant financial support to help businesses on Brick Lane survive COVID-19. Businesses in the centre of London have been overlooked and as a result, they are suffering. It also asks that the unique cultural and social heritage offered by Brick Lane’s Indian restaurants should be recognised and renewed, with investment and training within the London Plan. As well as to develop borough planning support, ideally through ground-floor property usage restrictions, capping of rents, extension of licensing hours and investment in the night time economy. And to provide training and support to restaurant owners to adapt to a changing business environment.

Finally, the report recommends that city and borough planners should recognise the hidden social and economic costs of regeneration and global investment in east London, and secure affordable social housing for low-paid workers and affordable workspaces. As well as to broaden heritage support to formally recognise the unique contribution of the Bangladeshi community to the history of Brick Lane and east London, and global London, in heritage institutions, educational provision, and the material fabric of the street.

Banglatown is an important and integral part of both Brick Lane’s history and the history of the Bangladeshi community in Britain. It also highlights the little-known history of the East End of London, and Britain itself.

New Year New Challenges New Solutions?

What does the future look like for the hospitality industry?

Top restaurateurs give their verdict

‘Unprecedented’ is perhaps the most fitting word to describe this rollercoaster of a year – a turbulent year where the hospitality industry has undeniably been one of the sectors hit hardest.

Frequently changing government strategies – in turn boosting and hampering the sector – have left restaurateurs with no choice than to adapt and make many sacrifices to survive, with some even shutting their doors for good.

As we shut the door on this incredibly tough year, and look toward to a new one, many are wondering what lies ahead for the hospitality industry. With the prospect of multiple vaccines and mass testing assuring a gradual return to normality by next spring, there’s hope within the sector that the restaurants we know, miss and love will return to our cities and neighbourhoods.

But until then, will owners be looking to adapt to new ways of working? And, if so, in what ways?

To get a better idea, we spoke to leading restaurateurs to get their predictions for the future of eating out.

Capturing data

With such uncertainty surrounding consumer habits in the New Year, investing time and money into data capturing is a useful way to enhance and bolster a restaurant’s demographic.

Ruhel Hoque, from The Indian Ocean in Cambridge, sees this as a key strategy for him to draw in the right type of customer: “I do all digital marketing and social media, targeting specific customers individually with personalised offers,” he says.

“I’ve updated our data capture so I can get more information about customers from google, phone calls, email and SMS marketing. My free WIFI also works as a data capture for customers, so I know what they like and what they don’t like.”

Ruhel views digital marketing, ultimately, as a crucial tool for keeping customers interested: “Restaurants will always be a luxury which people can do without; we are a treat and not a necessity like supermarkets or corner shops,” says Ruhel.

“We have to market ourselves so that, with all of this doom and gloom, we’re a good way to forget about our collective problems. Our industry has a shortage of skilled people – chefs, sous chefs and so on – and as a result I’ve invested heavily in technology to stay ahead.”

Leaving Europe

Another strain on the restaurant industry in the near future is the reality of leaving the European Union.

Mr Ataur Rahman Lyak, owner of Rajdoot Tandoori in Guildford, shares his concerns over the fluctuating prices of products, as well as European workers’ involvement in the sector:

“We have difficult times ahead of us,” he explains. “The number of people losing jobs means their pockets are shrinking – and coming out of the European Union is another big worry. “We buy a lot of produce from Europe, so there are concerns that prices will get much higher once we leave. Also, there is currently a large volume of European people working here in the sector, and I feel that will reduce quite significantly by December or sometime in the new year.”

Technology boost

Most restaurateurs would agree that technology is the way forward for the industry – certainly in the view of Mr Lyak: “Restaurant; technology is very important for restaurant management systems and it’s only a one-time investment. I believe the tech is the future – especially as it’s becoming more reliable, with QR codes, ordering systems and so on,” he says.

“To thrive in this competitive market, you need good technology and equipment to support yourself, so then we can have smaller staffing costs. We are therefore planning on heavily investing in a lot of modern technology, such as online ordering systems, so that staff don’t have to take orders themselves.”

On the other hand…

The sector has seen a huge uptake in restaurant tech due to the pandemic, with most restaurants adopting some form of app ordering systems and QR codes to help with order-taking. Despite this, not all restaurateurs see technology as the only avenue to go down when it comes to a restaurant’s operation.

Jamal Uddin Ahmed, owner of Shozna Restaurant in Rochester, states he, for one, will continue to operate his restaurant manually: “At the moment we have all the PPE in place for customer service; we take orders from the table and our menus are disposable.

“We will continue to do everything manually, making sure it’s all safe,” he says. “Technology is very good but when it goes wrong, it’s a big headache for us. It’s a very busy restaurant so we can’t afford the system to go wrong.”

Ruhel Hoque, agrees on the use of QR codes: “We will keep QR codes and apps in the restaurant for the next year, although once everything fully goes back to normal, we’ll go back to providing physical menus.”

Fine dining in danger?

Another worry for the restaurant sector is the future of fine dining. For Jamal, he sees this particular type of dining in danger due to the inevitable high pricing which comes with running such a menu: “I think fine dining is in danger next year. For the last five years we’ve been doing it, but because it hasn’t been feasible this year, we had to cut it. One problem is the table spacing, and it’s also very expensive to run the fine dining menu compared to the normal one.” Jamal adds: “I don’t want to take the risk of operating two different types of foods and orders, because the regulations are so much stress – so we’ve only been operating with one, and fortunately it’s working well

for us.”

Appliances

With the pandemic taking so much control away from restaurateurs, something they can do to manage future operations is to invest in better appliances. Explains Ruhel: “I have invested lots of money in appliances. Before all this investment we only had people to do the work. But now we’ve got prep machines which can do an hour’s work in five minutes.”

“Our new ovens do multiple cooking at the same time. So, one person can actually do work previously requiring three or four staff. And then on the tandoori side, I’ve replaced the whole tandoori with a rational oven,” he says. “I’ve also invested in a dough machine which does all the work. It’s a very labour intensive and skilful job – and that’s done by machinery now.”

Takeaways

Many restaurateurs would agree that takeaway is currently a major priority. For Mr Lyak, he believes takeaway is “the biggest thing in the industry now”:

“I’m concentrating more on takeaway than the physical restaurant. The takeaway industry has grown much bigger and is more profitable if you can run with a proper system,” he says.

“Takeaway means less people, and increased returns. With restaurants, even if you have so much technology, you still need waiters to serve. With takeaway, the system automatically receives the order.”

Ruhel is similarly investing more money in tech to bolster sales: “We’ve recently invested in online ordering – an online ecommerce website – that does a similar job to Just Eat but at a bespoke level.

“I’ve adapted: before we had a phone, pen and paper, but now we have an integrated system with online ordering, and everything is done automatically,” says Ruhel. “That’s the way forward, really. I’m generally moving towards automation, but not to an extent of a McDonalds or a KFC.”

Carry on restaurants

Although takeaways have seen a huge uptake this year, Jamal remains committed to focusing his efforts on the restaurant next year: “We’ve had takeaways from the beginning, but I’m mainly still in the restaurant game. We’re a 140-seat restaurant and we’ve invested so much in the restaurant side, so we wouldn’t convert to a takeaway only or look at the future as being takeaway,” he says.

“It’s too much for me to lose because we have massive premises. If we tried to operate just on the takeaway side, it would be a big loss for me; it’s a three-floor storey building. If we’re just operating as takeaway, what would we do with the other two floors?” Jamal says.

“We’ve already refurbished the restaurant this year, so everything is Covid-19 compliant and hands-free. If you go the bathroom you don’t need to touch anything.”

Staff skills

For second-generation restaurateur Ruhel, whose restaurant has been in this industry since 1965, he sees the restaurant remaining “a very viable business at the moment” – although he believes there needs to be more focus in “attracting younger, more vibrant people into this industry”.

“You will always need staff. But the approach I have taken is reducing the skill level,” says Ruhel. “Before, the tandoori chef or someone of that calibre had a skill, how to cook produce, naan bread, chapati, spicing. But now what we have done here is document all the recipes with weights and measures so all this is easier to pick up by other staff.”

Reducing menus

Another alteration many restaurateurs have had to make is reducing menus, says Ruhel: “At a normal Indian establishment, you’d have a hundred or so dishes on one menu. At ours we only have 30 dishes. Over the pandemic, due to the shortage of staff and social distancing measures, we have drastically reduced the menu even more.” Does he hope to expand his menu, once things gradually return to pre-pandemic levels of service? “Yes, we hope to expand it again, but it all depends on the economy – it’s looking quite bad at the moment,” he says. “From the financial side, it will be a very difficult road to recovery. But we always remain optimistic.”

Madhus opened two more new restaurants

The Southall’s famous fine dining event caterer Madhus has turned 40. To mark 40 years of successful event catering Madhus is opening two more new restaurants. With this, the number of their restaurants will be four in total.

On early December 2020, the Madhus has opened their new restaurant inside The Grove Hotel in Watford. Their fourth branch will be opened at London’s Mayfair in February 2021.

Mr Sanjay Anand MBE, Founder and Chairman of Madhus told Curry Life, that while the new restaurant’s menu is consistent with others, the service and delivery would be unique exceptions. Madhus flagship Southall and Madhus at Sheraton Heathrow Skyline are two other popular restaurants.

This famous event caterer serves food at all major exclusive events, including No10 Downing Street, Buckingham Palace and it is also caterer for the Curry Life Awards.

TIKKA WEEK – NOT A DAY!

Surely the UK’s favourite food warrants a celebration lasting a week – or are you among the small minority who think a day would suffice?

That’s the burning question that has been exercising industry experts – as we wave a not-so-fond farewell to 2020 and cast our eyes forward to a better, more successful 2021.

Here’s why the majority of people favour a week-long celebration – in the shape of the well-established National Curry Week, held each Autumn for the past 20 years!

Strong support for week

Since being launched in 1998, National Curry Week has become a firm fixture in the calendar – offering strong support for the curry industry with the three-pronged aims of showcasing the nation’s favourite cuisine, celebrating and supporting varied components of the curry restaurant industry and raising money for poverty-focused charities.

Over the past 21 years, hundreds of restaurants, caterers, pubs and home cooks have come together for one week to celebrate all things curry cuisine and culture – including unique dinners generating funds for causes both at home and abroad – with next year’s event scheduled for 7-12 October 2021.

Yet, despite National Curry Week’s continuing significance, a British Curry Day has been mooted for early December by some people from the curry industry – a call which can only serve to divert focus away from the already well-established National Curry Week and which is receiving mixed reactions from the curry industry. This may be a good point to remind ourselves of the aims and values of the founder of National Curry Week two decades ago, curry pioneer Peter Grove – who many restaurateurs and industry leaders feel would be disrespected

by any dilution of the week-long celebration.

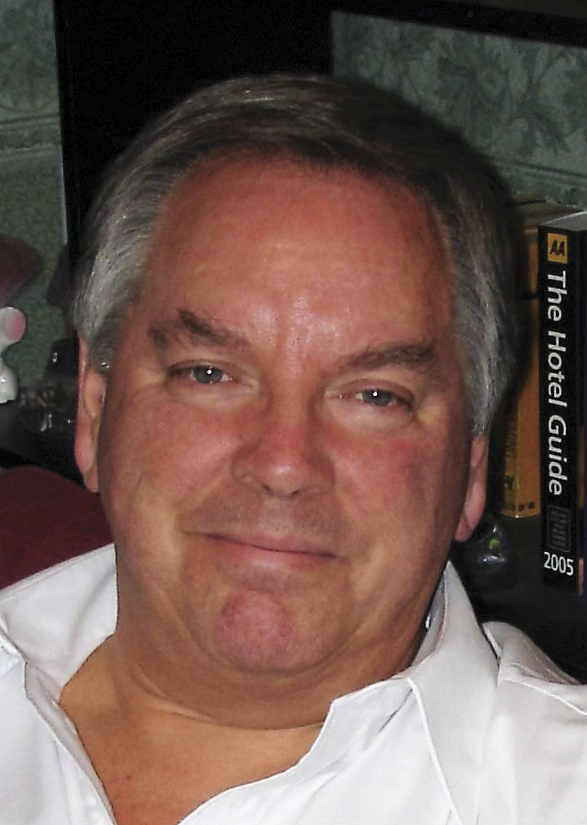

Late Peter Grove

Grove’s love affair with curry

The late Peter Grove, a well-known and established journalist, had a vision to promote awareness and appreciation of the curry industry after falling in love with curry cuisine.

In 1992, he started the Best in Britain Awards (BIBA) for the Asian restaurant sector -followed by National Curry Week in 1998 and Curry Capital of Britain in 1999.

Peter dedicated much of his rich and varied career to the curry industry: he worked with The Chartered Institute for Environmental Health (CIEH) for three years, running their National Curry Chef competition – as well as becoming President of The Federation of Specialist Restaurants and founder of The Curry Tree Charitable Fund and Menu Magazine.

Peter edited several travel and food guides, including The Real Curry Restaurant Guide from 1990. He appeared regularly on radio and TV as an expert in ethnic food and drink and co-wrote Curry Culture – a very British love affair with his wife Colleen as well as Flavours of History.

He also ran several major websites on ethnic food, drink and sport, which generated over 1 million visitors a month.

A prominent feature of National Curry Week has been the Curry Capital of Britain – a competition where cities race for the sought-after award through a combination of the quality of the food and fund-raising activities.

Held annually since 2001, the event was formed as a reaction to hostile publicity following racial unrest in areas of London – offering an opportunity to showcase UK cities promoting multi culturalism.

The focus was on cooperation between councils, restaurants and educational bodies to promote the curry industry, alleviate unemployment and promote community cohesion. Since the competition began, only five cities have been named Curry Capital: Bradford, Glasgow, Leicester, Birmingham and West London.

To this day, Peter is seen as a great Curry pioneer and an industry friend who has done so much for the curry world. Peter’s widow, Colleen, has spoken highly of the campaigns he inspired, and previously said: “I can think of no better lasting tribute than to continue the work he started with National Curry Week and The Curry Capital of Britain. Their role in highlighting the contribution made to the wider community by the Asian restaurant industry was a message that was very dear to him.” Now in its 22nd year, National Curry Week is still celebrated widely – and continues to showcase our beloved Curry Houses across the nation. So many are understandably now wondering: what is the point in introducing a new British Curry Day, when there is already a long-established, successful and widely recognised campaign dedicated to curry cuisine?

“We should be celebrating for longer – not shorter”

Many leaders within the industry echo the sentiment that, with an established national campaign already in place, the introduction of British Curry Day is unnecessary. Here’s what just a few have been saying…

Pasha Khandaker MBE

Pasha Khandokar MBE, former President of Bangladesh Caterers Association (BCA), says: “To be honest, I’m not sure why it’s necessary to introduce a British Curry Day now. Peter started National Curry Week a long time ago, when curry wasn’t that popular or an important part of everyday British life.

“Momentum was built up slowly, and now many leading industry brands, and even supermarkets, are united behind it. So, when you have an established week like this, I don’t find any reason to go small again – a week and a day makes a big difference.”

Pasha adds: “The curry industry is not having a pleasant time now due to challenges of the pandemic. Yet British curry remains the most successful food and has created millions of curry lovers in this country, it’s a part of people’s lives and they cannot live without curry.”

“If you want to see a strong post-Covid recovery, as an industry we should unite behind National Curry Week, plan better for our business and create mass and broader appeal for people to enjoy and support curry business more.” Pasha ultimately believes in celebrating all that British curry represents for longer, not shorter. “We like to see the curry industry looming larger and going forwards, not backwards,” he added.

Kingfisher

“We expect National Curry Week’s wonderful tradition to continue for another 20 years”

Kingfisher Beer, the world’s No. 1 authentic Indian beer brand and National Curry Week sponsor, staunchly supports the continuing work of National Curry Week – explaining: “We have been loyal supporters of National Curry Week ever since Peter Grove launched it over 20 years ago. When Peter sadly passed away in 2016, his widow, Colleen Grove, asked Kingfisher whether we would like to continue his work. Since then, we have been keeping his legacy alive.”

“National Curry Week is a time to honour the Nation’s favourite dish and to support the British curry industry. We have done this in a multitude of ways, from Indian street food markets to the creation of Curry Top Trumps and cookbooks. We expect this wonderful tradition to continue for another 20 years!” says, Shaun Goode, Chief Operating Officer of KBE drinks representing Kingfisher Beer Brand.

“Take the National Curry Week to even greater heights!”Restaurateurs within the industry likewise oppose the idea of a truncated celebration – instead preferring to see more effort being put into the already established National Curry Week.

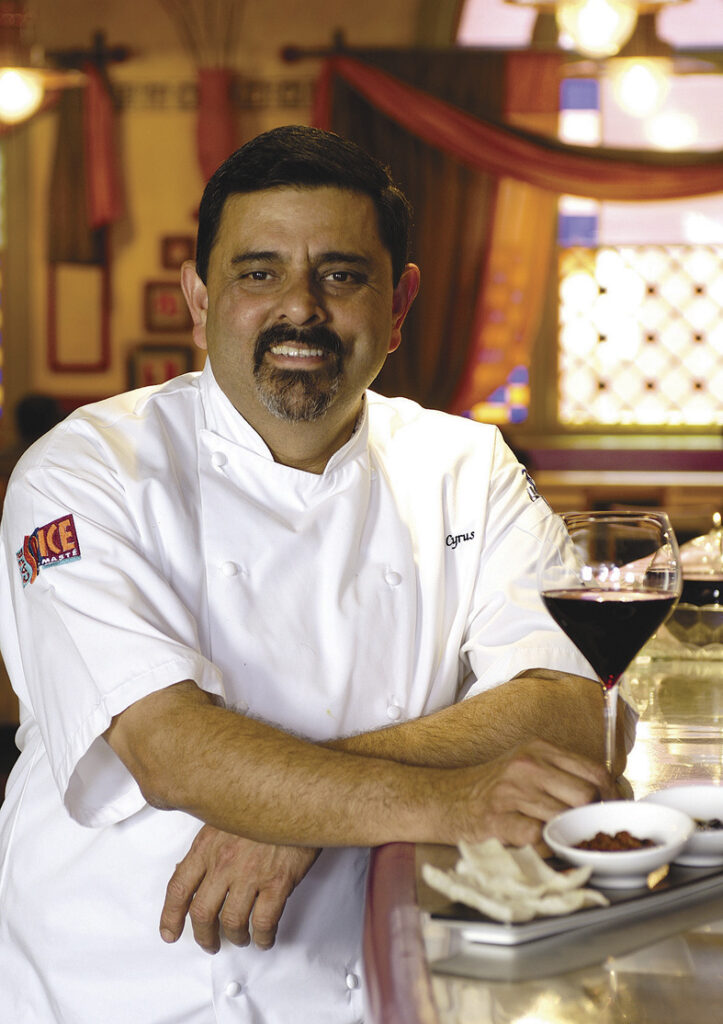

Cyrus Todiwala OBE

Cyrus Todiwala OBE, Chef at Cafe Spice Namaste in London, and Brand Ambassador for National Curry Week, says: “With National Curry Week having been established since the late nineties, and having gained so much publicity over the years, why do we need yet another initiative so soon after the original? I feel more muscle needs to be put behind the National Curry Week, to take it to even greater heights. Unity, I feel, is my preferred choice.”

While Cyrus may not view British Curry Day as going a backwards for the industry, he sees the new campaign as unwarranted: “When we already have a week to celebrate something, why depend on a single day? Instead, this day – if it is important – should be used to highlight the successes of National Curry Week and ask UK citizens to continue backing what everyone has done.

“It should be focused on reminding people of how great this industry is, how much it has done for hundreds of good causes and why we should, therefore, continue to celebrate it.”

Cyrus believes this new campaign, away from National Curry Week, also has the potential to undermine the great work done before it: “By having a British Curry Day, it can dilute the original ambition and therefore confuse people.

“Britain is a nation reaching a stage of charity fatigue. It is best to contain the urge for more and more support. I believe that people are more inclined to contribute and raise more funds when it’s less pushy.

“Overall, my feelings are to collectively give the National Curry Week greater impetus and drive it to an even higher level.

“When we already have a week to do something, why depend on a day? The new proposal undermines all the great work done before.”

M A Munim

M A Munim, current president of the Bangladesh Caterers Association (BCA), the oldest and main organisation representing the Catering Industry run by ethnic Bangladeshis since 1960s, views National Curry Week as the only national platform within the Curry Industry where people can come together to celebrate their love of curry.

He says: “We are already celebrating British curry by actively participating in National Curry Week – and we’ve done so every year for over two decades – so there is no point to also have a British Curry Day. I see it as contradictory.

“It also undermines the great work done by our pioneers over the last two decades,” he says. “We will continue to support and promote the National Curry Week and see do not see any justification for a new British Curry Day.”Not all those within the industry view British Curry Day as necessarily detrimental to the Curry Industry, however.

Tofozzul Miah

Tofozzul Miah, the current secretary general of the British Bangladesh Caterers Association, sees no harm in another one-day curry day.

“If it is done in a fair way; it’s better than bad for the industry”: People will talk about our industry, they will talk about our food,” he believes.

“Our curry is in every home from Docklands to Scotland. Despite having a week called National Curry Week, the one-day Curry Day will do no harm, as Curry Week is old and so well established,” says Tofozzul.

Shahanur Khan “Weeks are better than one day – customers become more aware!”

Shahanur Khan, the founding secretary general of the British Bangladesh Caterers Association (BBCA), says: “Since we already have a curry week called National Curry Week, I think it’s better to continue with this one. We were told that Curry Day is only meant to celebrate coming out of the lockdown; a weekly celebration is much better.”

“Weeks are better than one day because they raise greater awareness among people,” says Shahanur. “As customers become more aware, it encourages them to patronise restaurants and takeaways.

“Especially if it’s a week, if a customer misses one day, another day they can go, due to publicity on social media, local newspapers and so on. If someone wants to celebrate a particular day, we don’t really understand what vision he/she is pursuing.”

“Ultimately, we shouldn’t be brushing off the years of hard work and progress Peter Grove made in promoting the curry industry. “We should collectively continue to support National Curry Week as Peter Grove’s legacy – and do the right thing by giving credit to where it is due.”

Oli Khan MBE

While some may view a new national campaign as harmless, others also argue it will damage the curry industry if it seeks to benefit the individuals involved, rather than the industry as a whole:

“If British Curry Day is doing something good to promote the industry, then that’s fine, but my fear is that they are promoting only themselves, and not the industry,” Chef Oli Khan MBE says.

Oli, who set the world record earlier this year for the largest Onion Bhaji, is therefore not backing British Curry Day, nor its so called ‘Back the Bhaji’ campaign:

“National Curry Week has been running for quite some time now – and being a former secretary general of BCA (Bangladesh Caterers Association) when I was in the office, we signed a lifelong partnership with the National Curry Week campaign. We have established many promotions ever since. So, with National Curry Week already firmly in place, I don’t think there is any necessity to have another event.”

Khan also feels apprehensive about British Curry Day’s lack of communication with industry representatives: “With a national campaign like this, it needs to be promoted way before its launch; I first heard about it less than a week ago, just after the website launched, which doesn’t make sense to me.

“It has to be promoted widely beforehand and the industry has to have been informed – you can’t just run this as an individual as it’s a national issue. To raise your voice, you should call a meeting with all the representatives and organisations of the curry industry to discuss.”

As well as the British Curry Day’s lack of promotion prior to launch, Khan sees the timeframe of one single day as inadequate: “Even National Curry Week could have more time and that’s already a week – so why decide to hold for only one day?

There are 12,000 curry houses in the United Kingdom – so any national issue which helps the industry should be done collectively, rather than by an individual.”

“My fear is that they are promoting only themselves, not the industry”Many other voices in the industry also agree that British Curry Day’s small timeframe is the most significant issue when it comes to raising awareness.

British Curry Day

On the other hand, George Shaw, press spokesman for British Curry Day, says: “British Curry Day commemorates the lives and achievements of those restaurateurs and chefs who created our unique British Curry fusion in the 1960s and ‘70s.

“The day allows the younger generation of restaurant owners to remember their history and celebrate those early ‘curry pioneers’, so many of whom have been lost during the coronavirus pandemic.

“Despite hospitality businesses being devastated by repeated lockdowns, the curry has shown its usual generosity to local charities and good causes. A last-minute government extension of lockdown restrictions, meant that many restaurants remained closed to eat-in customers and planned fundraising meals had to be cancelled or curtailed.

“Nevertheless, the inaugural British Curry Day was deemed a great success by restaurants and customers alike. Many owners got behind the #BackTheBhaji campaign, donating the cost of the starter sold on the day, to their chosen charity. The onion bhaji is symbolic of the unique fusion of ‘British Curry’, created by those curry pioneers.

“These people came to a strange foreign land at the invitation of the British government and through their own endeavours and sheer hard work – often enduring blatant racism from post pub-closing time drunks – built a special industry, which is now an integral part of British society.” “Next year British Curry Day will be held 1st December 2021,” adds George Shaw.

Read more

Architectural splendours of Imperial India

The British had a lasting impact on Indian architecture, as they saw themselves as the successors to the Mughals and used architecture as a symbol of power. They brought in the world view, which made the indigenous architecture more vibrant and was later known as Indo-Saracenic architecture.

In a country with a history as old as India, the architectural heritage of the two centuries is hardly a summation of the past, especially when, the distant past is easier to recognise and appreciate that the recent past.

Indian subcontinent has been invaded ever since the times of Aryans. The invaders always attracted by richness of her natural resources, craftsmanship of her countrymen and glory of an already flourishing reign. The Europeans interest with India persisted since the classical times. The expedition of Vasco da Gamma to discover India in 1498 to the Dutch in 1590 and then the East India Company in 1600. Like all other aspects, colonization of Indian also had an impact on architecture style. With colonization, a new chapter in Indian architecture began.

Europeans brought with them their world view and a whole understanding of European architecture Neo-Classical, Romanesque, Gothic and Renaissance. The Portuguese architecture adapted the country’s climate appropriately, giving rise to Iberian galleried patio house, the Baroque churches of Goa, Se Cathedral and Arch of Conception.

The Danish influence is evident in Nagapatnam, which was laid out in squares and canals and also in Tranquebar, now Tharangambadi in Tamilnadu and Serampore in West Bengal. The French gave a distinct urban design to its settlement in Pondicherry by applying the Cartesian grid plans and classical architectural patterns.

However, it was the British who left a lasting impact on the India architecture. They saw themselves as the successors to the Mughals and used architecture as a symbol of power. When the British government had to consolidate its position in India, a whole new architecture was developed.

In the eclecticism of the age, English designers, disgusted with the classical and mediaeval styles of Europe’s past thought fit for his particular purpose, had turned back to the native vernacular traditions and produced the so-called ‘Free-Style’, hybrid but non-historicist.

However, it is particularly difficult to see colonial buildings as being a part of our past since even today; they are in active use in India. Indo-British architecture is characterised by structures which are monuments and many functional buildings which have monumental characteristics. Writer’s building in Kolkata, the Delhi Town Hall, the New Delhi secretariat, the Victoria Terminus now rechristened as Chatrapati Shivaji Terminus in Mumbai and many more which are now termed as “Heritage Buildings’, continues to serve the nation and serves as a testament of the triumphant of Britain’s conquest of India.

Erstwhile Bombay, Calcutta and Madras, now Mumbai, Kolkata and Chennai, and of course Delhi happens to have the largest culture of colonial structure in India, since they were the capitals of the three British presidencies, and Delhi from 1912 the capital of the empire.

Delhi’s morphology has the stamp of two imperial decision – that of Mughal’s decision to shift their capital from Agra to Delhi and later that of the British from Calcutta. Imperial Durbar at New Delhi was inaugurated by the British in 1931. Like Calcutta, it was stamped with the hallmark of authority and like most other seats of British power in India it stood apart from its predecessors.

The prevailing enthusiasm of Anglo-Indian imperial designers for the synthesis of eastern and western styles quailed before the problem of assimilating an urban order, devised in accordance with the principles of the modern English Garden City, and the vital chaos of Shahjahanabad: the latter seemed to be the very embodiment of all the evils of laissez-faire growth that the formulators of the Garden City movement most specifically deplored.

Sir Edwin Lutyens, who is credited for designing New Delhi, had arrived in India to undertake this great work had scant respect for the subcontinent’s architectural legacy. His views grew only the more derogatory with first-hand familiarity – especially with the Anglo-Indian Imperial hybrids developed by his immediate predecessors, but also with the traditions of ‘veneered joinery’ from which those hybrids were drawn.

Lutyens’ imperial eclecticism ranged from Wren’s St Stephen’s Walbrook (for the Viceroy’s library) to the Mahastupa at Sanchi (for the central cupola) and the chahar bagh. However, at the end of his trip, he took in the ubiquitous Indian ‘chattriand chadya’, cross-fertilized acanthus and volute with padma and bell for his Order and tethered Indian elephants at salient portal corners where the great ancient Mesopotamian monarchies had ceremonial syncretism winged monsters.

New Delhi as envisioned by Lutyens, was laid out five-kilometres south of Old Delhi on a well-drained site standing slightly above the level of the surrounding plain. The resulting complex is a spacious, attractive, and carefully planned city, with broad, tree lined avenues and many open areas, parks, gardens, and fountains.

Many of New Delhi’s best-known landmarks lie on a line running east to west through the city. The line starts at the National Stadium. Then it passes through the Children’s Park and the War Memorial Arch along the impressive Raj Path, through Central Vista Park, to Rashtrapati Bhavan (the residence of the president of India). A similar line running north-south, known as “Janpath,” goes from the main shopping centre, Connaught Place, to residential suburbs. Several districts retain their own character. The Civil Lines, originally laid out to house British colonial officials, is now a residential area for well-off Indian government officials.

On the other hand, the hybrid aspect of the style devised by Sir Scott for Bombay – though still essentially foreign and historicist – was a crucial pointer for builders to move away from a narrow cultural chauvinism towards Indian traditions. To that extent, it was reformative. However, the synthesis were to evolve, was far from rejecting overt allusion to the monumental styles of the past, added a resounding new dimension to historicist eclecticism in a truly imperial style.

The energetic Governor, Sir Bartle Frere of which Scott’s buildings were so significant a product, launched a public building campaign in Bombay in the second half of the 1860’s. The campaign opened with the Decorated Gothic scheme for the rebuilding of St. Thomas’s Cathedral by the Government Architect, James Trubshawe. This was only partially realized, but Trubshawe made a weighty contribution, in collaboration with W. Paris, in the General Post and Telegraph Office of 1872.

Of other landmarks produced by the campaign, William Emerson’s Crawford Markets – in an elementary northern Gothic delineated in the various coloured stones, which contributed so much to the success of the Gothic Revival in Bombay – reflected the ideals of the early design reformers at home more nearly than any other prominent Anglo-Indian building of the period.

For the Public Works Secretariat, Colonel Henry St Clair Wilkins, Royal Engineers, followed Scott’s lead with a Venetian Gothic design in 1877 and his colleague Colonel John Fuller mixed Venetian and early English for the stupendous High Court of 1879. The culminating masterpieces of the series, increasingly hybrid in style, are Frederick Stevens’ works, especially Victoria Terminus, the headquarters of the Great Indian Peninsular Railway.

Other famous landmarks in Mumbai are the Gateway of India. This huge arch commemorates the visit of King George V to India in 1911. The original white plaster design was replaced in 1927 by an arch of yellow stone in a mixture of Gujarati, Islamic, and European architectural styles. Other public buildings in Western neoclassical style include the Mint and the Town Hall.

While the attention of Scott and his Bombay followers was focused on Venice, the Government Architect Walter Granville ruptured the Classical decorum of Calcutta with an excursion into the arena favoured by Street at home and based the construction of Calcutta High Court (1872) on the Cloth Hall at Ypres. He also showed his versatility – not only at turning a corner – in the splendid General Post Office which, if classical in the purity of its forms, is certainly Baroque in scale and movement. For the Victoria Memorial at the other end of the Maidan, William Emerson embarked upon a quixotic attempt to rival the Taj Mahal. It was built of a similar luscious material but the alien forms, extruded from post-Bramante schemes for St Peter’s, Rome, hover between Mannerist and Baroque.

The Victoria Memorial, built between 1906 and 1921, is a huge structure in the Renaissance style, faced with white marble. It seeks to mingle classical, Western, and Mughal influences. The memorial contains Queen Victoria’s piano and writing desk and a fine collection of portraits of Anglo-Indian leaders. Another interesting structure is the Ochterlony Monument, a granite column 46 metres high.

In Calcutta and Madras such are the mansions and club houses of Chowringhi and Adyar, respectively, with their high ceilings and verandahs. Native merchants went even further with their houses. Most spectacular by far, is the Zimindari Mullick’s ‘Marble Palace’ in Calcutta, with its astonishing classical interpretation of diwan and court.

Many imposing structures still stand as monuments to British rule in India. They include the Raj Bhavan, the official residence of the governor of the state of West Bengal, which was modelled on Kedleston Hall, a great house in Derbyshire, in the United Kingdom. The Writers’ Building, a civil service headquarters, and the High Court are fine buildings in the Gothic style. The General Post Office and the Town Hall are built in neoclassical style.

Read more